The Myth of Pure Evil

Fear begets Anger

Anger begets Hatred

Hatred begets Cruelty

Cruelty begets Suffering

— peaceandlonglife

Roy Baumeister (1953)

Social Psychologist, Queensland University

[The myth of pure evil posits a] force, or person, that seeks relentlessly to inflict harm, with no positive or comprehensible motive, deriving enjoyment from the suffering of others …

It maliciously and gratuitously seeks out unsuspecting, innocent victims from among the good people of the world.

It is

- the eternal other,

- the enemy,

- the outsider,

(pp 74-5)

[In reality there] are four major root causes of evil, or reasons that people act in ways that others will perceive as evil.

Ordinary, well-intentioned people may perform evil acts when under the influence of these factors, singly or in combination. …

- The first root cause of evil is the simple desire for material gain, such as money or power. …

- The second root of evil is threatened egotism. …

- The third root of evil is idealism. …

- The fourth root of evil is the pursuit of sadistic pleasure.

[However,] only about 5-6% of perpetrators actually get enjoyment out of inflicting harm. …

The answer is that violent impulses are typically restrained by inner inhibitions; people exercise self-control to avoid lashing out at others every time they might feel like it.

The four root causes of evil must therefore be augmented by an understanding of the proximal cause, which is the breakdown of these internal restraints.

(pp 376-7)

A common and important cause of evil is the quest to avenge blows to one's pride.

Dangerous people, from playground bullies to warmongering dictators, consist mainly of those who have highly favorable views about themselves.

They strike out at others who question or dispute those favorable views.

(p 135)

[Most] violent people have high opinions of themselves, but most people with high opinions of themselves are not violent.

Violent people are an important but distinct, atypical minority of people with high self-esteem.

The most potent recipe for violence is a favorable view of oneself that is disputed or undermined by someone else—in short, threatened egotism.

(p 341)

The individualism of modern American society leads directly to worship of self-esteem and contempt for guilt. …

Self-esteem is better for the individual and worse for the community, and so Americans prize self-esteem.

Guilt is better for the community and worse for the individual, and so they detest guilt.

The American attitude that values the rights of the individual above the community's best interest apparently contributes to high levels of happiness contributes to individual freedom, and deters tyranny.

But it also promotes violence, along with oppression and individual forms of evil.

(p 313)

Egotism is … on the rise, especially now that modern morality has abandoned its religious commitment to humility and the condemnation of selfishness.

At the international level, one has to worry about Russia, whose rapid loss of global prominence and prestige is reminiscent of the humiliations that pushed Germany toward World War II. …

In the United States, the [national trend is] toward pursuing self-esteem and relaxing self-control.

As long as this trend predominates, it seems safe to expect that individual crime and violence in the United States will be high. …

Idealistic violence is difficult to forecast.

Christianity no longer seems to have the force to set off holy wars, but Islam does.

(p 384)

[All] over the world, regardless of culture or background, the same biological group is responsible for the bulk of the violence: young males from puberty through the prime age of reproductive potency.

(p 381)

The tendency to align with one's fellows and feel hostile toward potential opponents and rivals seems almost ineradicable. …

Yet culture can exert a great deal of influence in teaching people how to express and control their aggressive impulses. …

Equalizing opportunity can perhaps reduce the tendency to resort to violent means as a way of achieving material gain, although there is no very convincing proof of this.

Decreasing the emphasis on pride, self-esteem, and public respect, or providing multiple and clear criteria for proving oneself, may work against the tendency to use violence to maintain one's face.

A strong cultural belief in the rights of individuals and in the inability of noble ends to justify violent means can help prevent idealism from fostering brutality.

(p 382)

Future generations are likely to look back on people living now as evil, because of the profligate use of the planet's limited and dwindling resources. …

[But, unlike] the slave traders or warmongers of past eras [it will be future populations who] will be our victims …

The future will have its own version of Satan, and it is likely to be you and me (and our governments).

But, like most perpetrators, we do not see ourselves as doing evil.

(p 385, emphasis added)

[While the] victim's perspective [needs to be temporarily] suppressed for the sake of [understanding] the perpetrator, [it] is essential for making a moral judgment of the perpetrator.

It is a mistake to let moral condemnation interfere with trying to understand — but it would be a bigger mistake to let that understanding, once it has been attained, interfere with moral condemnation.

(p 387)

(Evil: Inside Human Violence and Cruelty, W H Freeman / Holt, 1997 / 2001)

Supply and Demand

[Gregoire M Afrine] testified today that the I G Farben combine purchased 150 women from the [Auschwitz] concentration camp, after complaining about a price of 200 marks (then $80.00) each, and killed all of them in experiments with a soporific drug. …

He told the American military tribunal … that he was employed as an interpreter by the Russians after they overran the … camp in January 1945 and found a number of letters there.

[Some of the letters were] from Farben's "Bayer" plant to the Nazi commandant of the camp.

These excerpts were offered in evidence:

- In contemplation of experiments with a new soporific drug we would appreciate your procuring for us a number of women.

- We received your answer but consider the price of 200 marks a woman excessive.

We propose to pay not more than 170 marks a head.

If agreeable, we will take possession of the women.

We need approximately 750. - We acknowledge your accord.

Prepare for us 150 women in the best possible condition, and as soon as you advise us you are ready we will take charge of them. - Received the order of 150 women.

Despite their emaciated condition, they were found satisfactory.

We shall keep you posted on developments concerning the experiment. - The tests were made.

All subjects died.

We shall contact you shortly on the subject of a new load.

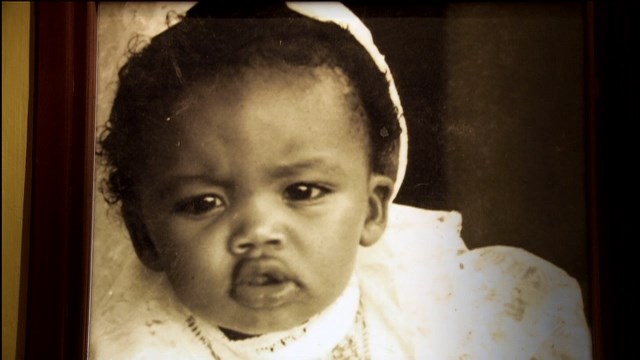

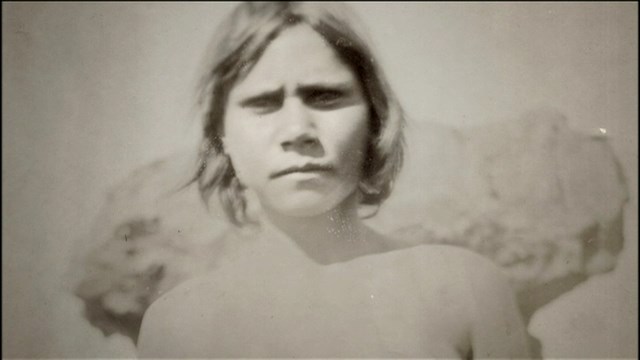

The First Australians

Rachel Perkins: Director, Writer and Producer

There is No Other Law

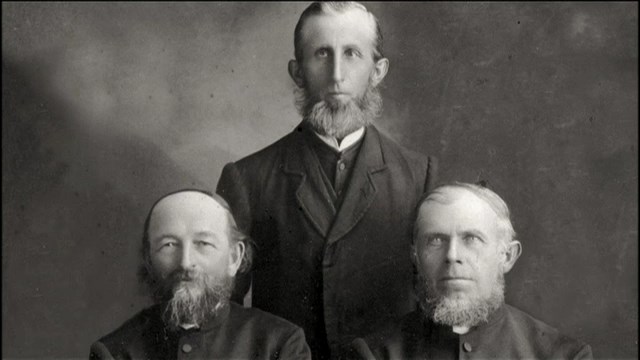

William Willshire [Colonial Police Constable]:

Men would not remain so many years in a country like this if there were no women.

And, perhaps, the Almighty meant them for use, as he has placed them where pioneers go.

What I am speaking about is only natural, especially for men are so isolated where women of all ages and sizes are running at large.

Astor Kempel [German Missionary]:

It is indeed shameful that the whites degrade themselves so much as they do — whoring with the native females …

And for this mean purpose, they use not only full grown females, but even mere children.

Unhealthy Government Experiment

A O Neville (1875 – 1954) [Chief Protector of Aborigines, Western Australia]:

Are we going to have a population of one million blacks in the Commonwealth?

Or are we going to merge them into our white community and eventually forget that there were ever any aborigines in Australia?

A Fair Deal For A Dark Race

Dougl Nicholls (1906 – 88) [28th Governor of South Australia]:

Australian natives are not a primitive people.

But a people living in primitive conditions.

They are entitled to a better deal than they are receiving from the white man.

If, given the opportunity, they could fly high.

But they have been denied their rights by being kept a race apart.

(SBS Television, 2012)

Official Development Assistance as a percentage of Gross National Income.

Australian ODA (red) has fallen by 31% since 2012 (from 0.36% to 0.25% of GNI) at the same time as the OECD average (black) rose by 14% (from 0.28% to 0.32%).

UN ODA target is 0.70%.

(Development Assistance Committee, OECD, 2016)

Contents

The Myth of Pure Evil

Tony Abbott: The Logic of Bigotry — Muslims, Terrorists, and Refugees

Anywhere but here

The Annual Holocaust

Non-Refoulement

The Ethics of Asylum Seeker Policy

Expert Panel on Asylum Seekers

UNHCR Assistant High Commissioner for Protection

Temporary Protection

A Well-Founded Fear of Persecution

- Boat Person, TED Radio Hour, NPR, 11 October 2013.

Tan Le. - Asylum seekers: drowning on our watch, Background Briefing, ABC Radio National, 1 September 2013.

- Refugees: Where Do They Come From?, Perth Writers Festival, 18 March 2013.

- A more ethical and realistic conversation: the Australian debate about asylum

seekers and refugees, Think Piece, St James Ethics Centre, September 2011.

Tim Soutphommasane: PhD, Fellow, St James Ethics Centre

Introduction

Public Opinion

[The] hostility that Australians have towards asylum seekers seems to be directed in particular at the spontaneous arrival of asylum seekers on boats.

The same level of concern doesn’t appear to exist with respect to asylum seekers who arrive by air …

In the five years to the end of [2010,] Australia received 15,226 boat arrivals (compared with Greece’s 56,180, Italy’s 91,821, Spain’s 74,317 and Yemen’s 185,810). …

[Essential Media] found that 38 percent of voters believed that boatpeople comprised at least a tenth of Australia’s migrant intake (with ten percent believing they comprised half or more).

In fact … Australia’s humanitarian program in 2009-10 [accepted] 13,750 people, compared to 168,700 in the migration program …

(p 2)

The Politics of Boatpeople

[Bipartisan] consensus broke down with the political impact of Hansonism in the 1990s.

Especially since the Tampa incident of 2001, we have seen asylum seeker policy particularly subject to a much more nakedly political contest.

Both major political parties feel that any retreat from a hardline stance on unauthorised boat arrivals will result in savage electoral punishment.

Much like the issue of “law and order”, political parties seek to outbid each other on how strong they are on maritime national security and how ruthless they are towards people smugglers [and boatpeople.]

A Lowy Institute poll [reported] that 86 percent of respondents believed that[Boatpeople] pose a potential security threat to Australia.

[On the other hand, an] Age-Nielsen poll showed that a majority of respondents believe asylum seekers who arrive to Australian territory by boat should have their claims for refugee status processed onshore. …

In any case, politicians are worried about a backlash from that section of Australian voters who indeed fear the boats — particularly those who live in marginal seats.

[There may be] a conflation of concern about unauthorised boat arrivals and concern about population growth.

Given that many voters mistakenly believe that those granted refugee status comprise a significant proportion of the annual migrant intake … the boatpeople issue has become a vehicle for broader anxieties about population growth and quality of life.

This seems especially the case in outer metropolitan areas of Sydney, Melbourne and the Gold Coast growth corridor, where population growth pressures are perceived to be acute. …

[The 1951 Refugee] Convention binds its signatories not to impose penalities, on account of their mode of entry or lack of authorisation, to a territory, where they have a well-founded fear of persecution.

Article 33 of the Convention imposes a duty of “non-refoulement”, which states that a refugee shall not be expelled or returned to a country where his or her life would be threatened on account of their race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.

(p 3)

The ethics of membership

In 2009 Australia only received and processed 6,500 asylum claims, compared to the 51,120 processed by the Nordic countries of Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland and Iceland (whose combined population of 25 million is not much larger than Australia’s 22.5 million).

Policy dimensions: Mandatory detention and regional frameworks

… Australia is the only country in the world to pursue a policy of mandatory detention for all asylum seekers who arrive by boat.

While such a punitive approach may be justified as a measure aimed to deter boat arrivals, the evidence strongly suggests that detention does not have any such effect.

Yet consider the crude human cost of the current detention framework, which can involve people being held in a detention centre under no criminal charge, and without a clearly defined time limit.

Stories of hunger strikes, self-harm and rioting in detention centres, some of which are located in remote desert areas of Australia, reflect the sense of desperation incarceration can breed.

Public health experts have long spoken out about how mandatory detention is a recipe for mental illness, especially among child detainees. …

[Other] countries, including many which receive a far higher number of asylum seeker arrivals, adopt alternatives to mandatory detention.

In any case, it is anomalous that it is only asylum seekers who arrive by boat who are subject to mandatory detention; those who arrive by plane are not subject to the same regime.

(p 6)

[Public] sentiment remains deeply divided about the onshore processing of asylum seekers [possibly due to] some subliminal attachment to a notion of a Fortress Australia, which boats arriving from the north should not be able to penetrate.

(p 7)

Conclusions and Recommendations

The policy of mandatory detention

It is anomalous that asylum seekers who arrive by boat are subject to mandatory detention, while those who arrive by plane are not subject to the same regime.

This is a distinction that runs counter to the spirit of Australia’s humanitarian obligations as they exist under the Refugee Convention.

Moreover, mandatory detention causes significant harm to asylum seekers, many of whom are detained for years without any certainty about their fate.

Any detention of asylum seekers should exist only in so far as it is necessary to conduct health, security and identity checks.

There should be a phasing out of mandatory detention.

Onshore processing of the refugee claims of asylum seekers who arrive in Australia by boat

The most ideal response to the arrival of boatpeople would be to process their asylum claims “onshore”, on the Australian mainland. …

[This] would be best achieved with bipartisan political support … as it would be likely to lead to an increase in the number of boatpeople seeking to make it to Australian territory.

In such a scenario, political leaders must educate public opinion about asylum seekers and refugees, and avoid politicking over boatpeople.

[In the absence of such resolve,] a shift to onshore processing may carry the risk of undermining public acceptance of a significant, racially non-discriminatory immigration program, and of a multicultural Australian society.

Offshore processing of the refugee claims of asylum seekers who arrive in Australia by boat

Given the apparent lack of bipartisan political support for onshore processing, it is likely that Australian refugee policy will contain some offshore processing element.

This is far from ideal.

[Every] effort should be made to ensure that there are improvements to current policy. …

There should be legislated minimal standards for the treatment of all asylum seekers in any offshore processing centre, based on relevant human rights standards, with adequate legal protections.

A regional framework and taking in more refugees

Within our region … Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand contend with the vast majority of asylum seeker movements. It is important to ensure Australia bears a larger burden, if there is to be successful cooperation with our regional neighbours, particularly in stemming the arrival of asylum seekers by boat. …

Our regional neighbours are unlikely to engage in developing a credible regional response if they believe that Australia does not take its fair share of refugees.

Improving public debate and depoliticising the issue

There is considerable merit in proposals to establish an independent commission to facilitate informed public debate, and an independent authority to administer Australia’s humanitarian programs.

Such a move would be similar to the delegation of monetary policy to an independent Reserve Bank.

The politicisation of boat arrivals has been an unedifying and destructive development in the political culture.

[Unless and] until there can be strong bipartisan political leadership on this issue, it may be necessary to seek an institutionalised form of depoliticising this most divisive of issues.

(p 8) - Houston panel ignores the evidence on asylum seekers, The Conversation, 14 August 2012.

Sharon Pickering and Melissa Phillips. - Houston report: hard heads deliver $1 billion asylum seeker plan, The Conversation, 13 August 2012.

Charis Palmer: Editor. - There’s no evidence that asylum seeker deterrence policy works, The Conversation, 24 July 2012.

Sharon Pickering: Professor of Criminology, Monash University; Editor, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology. - Report of the Expert Panel on Asylum Seekers, Australian Government, August 2012.

Angus Houston, Paris Aristotle and Michael L'estrange.

Asylum Seeking: The Challenges Australia Faces in Context

Australia’s circumstances

For each protection visa granted to an asylum seeker onshore, the offshore [Special Humanitarian Program] component of the program is reduced by one place.

(p 24)

The Global and Regional Context

The Global Situation

- Afghans represent one of every four refugees in the world, with 95% of them located in Pakistan and Iran.

- Pakistan hosts the largest number of refugees worldwide (around 1.7 million, with another million unregistered), followed by the Islamic Republic of Iran (around 900,000).

- Of the estimated 1.6 million Iraqi asylum seekers in the world, the majority reside in neighbouring countries (around 1 million in Syria, 500,000 in Jordan, 50,000 in Iran and 30,000 in Lebanon).

- South Africa and Kenya each host refugee numbers in the hundreds of thousands.

The city of Dadaab in north-eastern Kenya hosts the largest refugee complex in the world, housing more than 559,000 registered refugees and several thousand more asylum seekers who are unregistered.

(p 61, emphasis added)

Global refugee numbers have remained relatively steady despite different crises and conflicts in the past decade.

In the same timeframe, the number of internally displaced persons (IDPS) worldwide has consistently exceeded refugee and asylum seeker numbers …

[In] 2011 an estimated 26.4 million people were considered internally displaced.

… IDPS have not crossed an international border to seek protection, even though they may be displaced for similar reasons as refugees.

[They] remain under the protection of their own government, even though that government may be the cause of their flight.

(p 63, emphasis added)

The Australian Context

… Australia remains a minor destination country for irregular migrants and asylum seekers [— receiving] 2.5% of global asylum claims in 2011.

(p 68)

Since late 2008, over 18,000 IMAs have arrived in Australia …

[The] only comparable time for this number and tempo of boat arrivals was … when 12,176 people arrived on 180 vessels in 1999 — 2001. …

[Since] 2000, an estimated 946 people have [been lost at sea] while attempting to reach Australia by boat, 604 of them since October 2009.

(p 69)

Asylum Caseloads And RSD Rates In Australia And Globally

Persons of Concern in the Middle East and South-East Asia regions

Table 19

(p 102)

Total persons of concern to UNHCR in selected territory/country of asylum by calendar year.

Source:

UNHCR Statistical Yearbooks 2006 to 2010; UNHCR Global Trends Report 2011.

The composition of the asylum caseloads in these countries is:- Iran — Afghan (96%) and Iraq (4%)

- Pakistan — Afghan (99.9%)

- Thailand — Stateless/Myanmar (99%)

- Malaysia — Stateless/Myanmar (92%%), Sri Lanka (5%)

- Indonesia — Afghan (67%), Iranian (10%), Somali (7%)

- Letter to Wayne Swan [Acting Prime Minister], 23 December 2011.

Tony Abbott.

For over a decade, we have consistently held the view that Australia’s border protection policies must include- offshore processing,

- Temporary Protection Visas and

- turning boats around where it is safe to do so.

- Asylum Trends — Australia: 2010-11 Annual Publication, Systems, Program Evidence and Knowledge Section, Department of Immigration and Citizenship, 2011, p 2.

Commonwealth of Australia.

Protection visa applications lodged

Irregular Maritime Arrivals Non-IMA Total 5,176 6,316 11,491 Final Protection visa decisions

IMA (p 34) Non-IMA (p 20) Grants 2,696 (89.6%) 2,101 (43.7%) 4,797 (66.4%) Refusals 313 (10.4%) 2,709 (56.3%) 3,022 (38.6%) Total 3,009 4,810 7,819

- Who are the asylum seekers? Rear Vision, ABC Radio National, 20 July 2011.

Stephen Castles.

[We] have, in Australia, this discussion about so-called queue jumpers …

There are seven million people [who need] resettlement, and … the world as a whole resettles 80,000 people a year.

[It] would take 90 years to resettle the people who today have already been in exile for five years or more [even] if no new refugees were added to that population …

So the idea of a queue is a total illusion.

Would you like to know more? - Boat arrivals in Australia since 1976, Social Policy Section, Australian Parliamentary Library, 25 June 2009.

Janet Phillips & Harriet Spinks.Phillip Ruddock (1943) [Australian Immigration Minister, 1996-2007; Special Envoy to the Prime Minister (Malcolm Turnbull) for Human Rights (Designate)]:

In October 1999, the Howard Government introduced Temporary Protection Visas (TPVs) …

What One Nation would be saying is that [asylum seekers] have no place in Australia.

They are only to be here temporarily.

But if you’ve chosen correctly, the people you bring in are likely to have been tortured, traumatised, and in need of support for rebuilding a new life.

Can you imagine what temporary entry would mean for them?

It would mean that people would never know whether they were able to remain here.

There would be uncertainty, particularly in terms of the attention given to learning English, and in addressing the torture and trauma so they are healed from some of the tremendous physical and psychological wounds they have suffered.

So, I regard One Nation’s approach as being highly unconscionable in a way that most thinking people would clearly reject. …

(Quoted in Singer & Gregg, How Ethical Is Australia?, 2004, p 67)

A TPV was valid for three years, after which time a person’s need for protection would be reassessed.

Holders of TPVs were provided with access to medical and welfare services, but given only reduced access to settlement services, no access to family reunion, and no travel rights. …

Approximately 11,000 TPVs were issued between 1999 and 2007, and approximately 90% of TPV holders eventually gained permanent visas.

In May 2008 the Rudd Government announced that it would abolish the system of temporary protection. … - Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs, Additional Estimates, Immigration and Citizenship portfolio, Hansard, pp 72-3, 24 February 2009.

Chris Evans: Senator (ALP).

From December 1999 to November 2010 there were only 2,900 arrivals, as compared with 3,000 before that. …

[There] were 6540 boat arrivals in the second year of the operation of the TPV regime. …

Our figures show that in that period the percentage of women and children went from around 25% to around 40%.

We saw more women and children taking the very perilous journey to come to Australia by unlawful boat arrivals. - Text of the 1951 Convention and 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, 1967.

United Nations High Commission for Refugees.

[By subjecting irregular maritime arrivals to mandatory detention and offshore processing, the Australian Government is failing to] accord to refugees lawfully in its territory- the right to choose their place of residence to move freely within its territory, subject to any regulations applicable to aliens generally in the same circumstances.

[and is in breach of its obligations by imposing]- … penalties, on account of their illegal entry or presence, on refugees who, coming directly from a territory where their life or freedom was threatened …

- [And by applying] to the movements of such refugees restrictions other than those which are necessary …

A Generous Open-Hearted People

For those who've come across the seas

We've boundless plains to share;

With courage let us all combine

To Advance Australia Fair.

— Peter McCormick (c1834 – 1916)

(No Advantage, ABC Four Corners, 29 April 2013)

(Lawyers representing five-year-old Iranian asylum seeker sue Government for negligence,

ABC Radio National Breakfast 20 May 2015)

'Which of the following four statements comes closest to your view about the best policy for dealing with asylum seekers trying to reach Australia by boat?'(Andrew Markus, Mapping Social Cohesion: The Scanlon Foundation Surveys 2016, Scanlon Foundation, Monash University and the Australian Multicultural Foundation, 2016) | |

| Turn back boats | 33% |

| Temporary residence only | 31% |

| Permanent residence | 24% |

| Detain and send back | 9% |

| Refused / Don't know | 4% |

John Winston Howard (1939) [Prime Minister of Australia, 1996-2007]:

[We] are a generous, open-hearted people; taking more refugees on a per capita basis than any nation except Canada. …

But, we will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come. …

- We do not behave in a way that causes people to drown and to die.

- We do not shoot people.

(Federal election campaign launch, City Recital Hall, Sydney, 28 October 2001)

[No] country will accept a fundamental undermining of its cultural identity in the name of accommodating people flows …

[On the other hand, we] should stop being apologetic about the advantages of British settlement …

(John Howard on threats to free speech and robust debate, Centre for Independent Studies, 10 July 2018)

Donald Trump (1946):

I think Islam hates us. …

There is an unbelievable hatred of us.

(CNN Interview, 9 March 2016)

George Orwell (1903 – 50):

April 4th, 1984.

All peoples who have reached the point of becoming nations tend to despise foreigners, but there is not much doubt that the English-speaking races the worst offenders.

(1939)

Last night to the flicks.

All war films.

One very good one of a ship full of refugees being bombed somewhere in the Mediterranean.

(Nineteen Eighty-Four, 1949)

Rebecca Huntley (1972):

More than once, [Australian discussion group] participants have suggested the best way to stop the boats is to blow a few out of the water.

(How Racist Are We?, Still Lucky, Penguin, 2017, p 82)

Andrew Jakubowicz {Professor of Sociology, University of Technology Sydney]:

It was as if they wanted to adopt a Churchillian stand …

We will fight them of the beaches!Pauline Hanson (1954):

We will stop them coming.

No matter what. …

[If] I can invite whom I want into my home, then I should have the right to have a say in who comes into my country.

(Maiden Speech, Australian House of Representatives, 10 September 1996)

Arnon Soffer (1935) [Professor of Geography, University of Haifa]:

[In] India they shoot [asylum seekers.]

In Nepal they shoot.

In Japan they shoot.

(Sharon Udasin, Defending Israel's Borders from 'Climate Refugees', Jerusalem Post, 15 May 2002)

Emma Lazarus (1849 – 1887):

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me …

(The New Colossus, 1883)

Patrick McGorry (1952):

Any decent Australian would be concerned about deliberately doing harm to people — knowingly [doing] harm.

Which is what [the 'no advantage'] policy does actually do.

('No advantage' policy may leave asylum seekers destitute: mental health experts, RN Breakfast, 8 May 2013)

Charles Dickens (1812 – 1870):

[Conscience] is an elastic and very flexible article, which will bear a deal of stretching and adapt itself to a great variety of circumstances.

(The Old Curiosity Shop, 1840-1, Oxford University Press, 1951, p 52)

Judith Brett (1949) [Professor of Politics, Latrobe University]:

[What John Howard offered] the people of Australia [was] protection from threat.

Now to protect from threat you have to convince people that there are threats out there.

And lots of people do believe there are threats out there. …

David Jull (1944 – 2011) [Chairman, Parliamentary Committee on Intelligence Matters; Liberal MP, 1984-2007]:

Our security people … have found that quite of few of those people who come in do have criminal backgrounds.

Peter Slipper (1950) [Parliamentary Secretary, Finance and Administration, 1998-2004]:

There's an undeniable linkage between illegals and terrorists.

Andrew Kirk [Senior Advisor to Amanda Vanstone, 1999-2004]:

We were getting a lot of calls from people indicating to us that we should send the navy out there and sink these boats. …

That we should … have been turning these boats around all along.

I was shocked at the hard line attitude of some of these callers …

[We] had uncovered a darker element in the Australian psyche …

Malcolm Fraser (1930 – 2015) [Prime Minister, 1975-1983]:

[People's] fears had been aroused.

[Fears] on the basis of race or religion, or coming from a place that we didn't know or didn't understand.

And if a government plays on those fears and magnifies those fears, then its a potent political force. …

Judith Troeth (1940) [Liberal Senator, 1993-2001]:

The 'Pacific Solution' was a most unfortunate name given historical connotations.

For me, there was a growing sense of anger that people could be treated like that in this day and age — especially when they had come to our country looking for refuge.

John Howard (1939):

That stopped the boats coming.

Nothing anybody says, nothing the Human Rights organizations say, nothing the Labor Party says, can alter that fundamental fact. …

[Asylum seekers who arrive by boat] presume on our generosity. …

Philip Ruddock (1943):

[A] number of children have been thrown overboard.

John Howard (1939):

I can't comprehend how genuine refugees would throw their children overboard.

Alexander Downer (1951) [Foreign Minister, 1996-2007]:

They will not be welcomed on the mainland of Australia and they will not be integrated into our community.

It's not going to happen.

Kim Beazley (1948) [Labor Opposition Leader, 1996-2001]:

You can't reward people for that sort of behavior.

ABC Presenter:

Mr Reith, there's nothing in this photo that indicates that these people jumped or were thrown …

Peter Reith (1950) [Defence Minister, 2001]:

You're now questioning the veracity of reports from the Royal Australian Navy.

I don't.

It's as clear as day … so do you still question it?

Do you?

ABC Presenter:

I'm a journalist, I'll question anything until I get the proof, that's my job.

Peter Reith (1950) [Liberal Member of the Australian Parliament for Flinders, 1984-2001]:

Well, I've just given you the evidence.

ABC Presenter:

No, you've given me images …

Peter Reith (1950):

Well … if you don't accept that, you don't accept anything I say.

John Howard (1939):

In my mind there is no uncertainty because I don't disbelieve the advice I was given by Defence.

Children Overboard affair:

The Australian Senate Select Committee for an inquiry into a certain maritime incident later found that no children had been at risk of being thrown overboard and that the government had known this prior to the election. …

[In 2007] John Howard asserted that

[The asylum seekers] irresponsibly sank the damn boat, which put their children in the water.(Wikimedia Foundation, 6 April 2014)

The Australian Gulag

Malcolm Turnbull (1954):

You have to remember that those [detention camps on Manus Island and Nauru] are managed by the respective governments, PNG and Nauru.

That's a fact.

Sarah Ferguson:

But are you not responsible for the people in those centers … as the Australian Prime Minister who runs the regime that holds them there?

Malcolm Turnbull:

Well, we don't hold them there.

We don't hold them there.

That is not correct.

We do not hold them there.

Sarah Ferguson:

So you don't feel responsible for them?

Malcolm Turnbull:

I am responsible for ensuring that our borders are secure …

There is a view that the Labor Party will take a weaker view on border protection …

Bill Shorten:

If we were to allow the people smugglers back into business people will drown at sea …

(The Leaders, Four Corners, 27 June 2016)

Immigration and Refugees

Nicola Henry and Karolina Kurzak

Of the seven million people who have migrated to Australia since World War II, over [500,000] have arrived under humanitarian programs, either as displaced persons or refugees.

Currently, one in four people in Australia were born overseas. …

The countries which currently provide the highest number of migrants to Australia are …

- New Zealand (20.2%),

- China (11.5%),

- the United Kingdom (8.6%), and

- India (8.3%).

Migration Program

In 2011-12, the number of visas granted … was as follows:

Migration Program:

- Skilled stream: 125,755

- Family stream: 58,604

Humanitarian Program:

- Refugee: 6004

- Other Humanitarian:

- 714 to people offshore under the [Special Humanitarian Program], and

- 7041 to people onshore

Australian Immigration Trends

Net overseas migration refers to … the difference in numbers between permanent and long-term [> 1 year] arrivals and permanent and long-term departures. …

- In 2011-12, net overseas migration was 197,200 persons …

- skilled migrants accounted for 39% of all permanent or ‘settler’ arrivals to Australia;

- family stream migrants for 27%;

- Humanitarian Program migrants for 5%, and

- Non-Program Migrants (consisting mostly of New Zealand citizens) for 29%; …

- [The number of overstayers —] people who arrived in Australia with valid temporary visas … but have overstayed [—] was estimated to be around 53,900 at 30 June 2010.

Net overseas migration now contributes to more than half of Australia’s population growth, whereas, in the past, natural increase was more prominent. …

The 28% fall in net overseas migration between 2008-09 and 2009-10 [in the context of the GFC, reversed] the trend established over previous years [by the previous] Howard Coalition Government.

(p 2)

Asylum seekers and refugees

[The] 1951 Refugee convention makes it clear that it is not illegal under international law to seek protection from persecution in another country, even if the entry is unauthorised. …

[Historically, 70-97%] of asylum seekers arriving by boat [in Australia] have been found to be genuine refugees. …

[Among] industrialised nations, Australia [ranks 17th out of 44 countries] for the number of asylum applications it receives [per capita.]

(p 3)

(Fact Sheet, The Australian Collaboration, December 2012)

Immigration Nation

In July 1979, [Malcolm Fraser agreed] to take 14,000 Indochinese refugees.

Ultimately, 70,000 [settled] here during his time as Prime Minister [of Australia (1975-83). …]

Boat people remain one of Australia's great fears. …

Since the Vietnamese refugee crisis around 20,000 boat people have arrived in Australia.

At the same time more than 3.5 million immigrants have made their home here, without provoking comment and largely with great success. …

Australia has one of the highest rates in the world of inter-marriage between different cultural groups. …

Since 1976 boat people have made up less than 1% of Australia's immigration intake.

Non-Refoulement

Frances Harrison [former BBC Foreign Correspondent]:

In England [there have been] about 92 cases [of failed Tamil asylum seekers, who were initially deported back to Sri Lanka, and then later] returned to the UK [after] having been tortured [— and then were granted asylum. …]

Bianca Hall:

Since August 13 [2012], the government has returned 1,004 Sri lankans who arrived on boats — 795 involuntarily.

(Asylum seekers sent home, The Age, 19 April 2013)

Phil Glendenning:

[The four asylum seekers] sent back to Columbia were all killed …

[Two] of them didn't make it out of the car park.

Nine were killed in Sri Lanka.

Four in Iraq.

Two in Iran that we know of.

In Afghanistan we can prove there have been 11 deaths.

We believe that number is far higher ‒ probably in the vicinity of 30. …

After the War

She lived in the east of Sri Lanka.

[Her] two younger brothers were forcibly taken by the Tigers to fight.

[They] went away hand in hand they were so young, they were teenagers.

And they never came back. …

[Then] she was encouraged to join the Tigers …

She never fought because there wasn't much fighting in the east by then.

[Instead,] she worked in an office, and gave them information about what [an] NGO was doing. …

[After] the war, she was asked to constantly report to the police station …

And every time she went, with her Dad to protect her, they would touch her all over her body, and they would pull her hair and man-handle her.

[One] day they took her into custody and gang raped her for several days.

She got out and went to hospital and her mother just sat on the bed hugging her on the hospital bed for 2 days.

[So] they sent her away … to try and get her away from … the police.

[One day,] her father disappears … and they find his body, beaten to death, in a ditch.

[Some time later] her Mum rings up and says:

Whatever you do, don't come home.[The] next day, she gets a phone call …

They're looking for you.

Come home, come home, your mother and your sister are dead![She] goes to the house and … finds the skeletons of her mother and her sister on a bed of ash in the house.

[She] can still see the trace of the fabric of her sister's dress …

[It] was one of her dresses that she had handed down to her.

She's [so distressed she] doesn't hide [and] the police pick her up again.

[This] time they keep her for 47 days.

[They] continuously gang rape her, including with her head in a bucket of water.

They beat her.

They starve her.

[Eventually a] relative manages to [buy her freedom …]

[She's taken] across the island at night — literally still wearing the clothes stained in blood and semen — [and put] on a little boat at midnight, on the west coast of Sri Lanka.

[She] gradually goes with these human smugglers from India to the Middle East, and finally lands in London.

[When] I met her [in London] she couldn't really tell her tale, she was so distraught. …

[She's] got cigarette burn marks [on her body —] that's how they brand people they keep in custody.

She's very pretty.

She's 26 years old. …

[She] just looks at the wall and wants to kill herself.

She says:

I'm to blame for my family all dying.[That] was November [2012.]

[We] were an ordinary Tamil middle class family …

I wanted to be a teacher.

So when politicians say everything is fine in Sri Lanka … it's all alright, I think of her. …

In England [there have been] about 92 cases [of failed Tamil asylum seekers, who were initially deported back to Sri Lanka, and then later] returned to the UK [after] having been tortured [— and then granted asylum. …]

Report of the Expert Panel on Asylum Seekers

Currently, at best, only one in 10 persons in need of resettlement will be provided with that outcome annually.

(p 38)

The city of Dadaab in north-eastern Kenya hosts the largest refugee complex in the world, housing more than 559,000 registered refugees and several thousand more asylum seekers who are unregistered.

(p 61)

Likely Costs Of The Panel’s Recommendations

[The] full establishment and operation of a regional processing capacity

- in Nauru accommodating up to 1,500 people would cost between $1.2 billion to $1.4 billion … including capital costs in the order of $300 million [= $800,000+ per person] …

- in PNG (such as on Manus Island) accommodating up to 600 people would cost in the order of $0.9 billion … including capital costs in the order of $230 million [= $1.5 million per person …]

- an increase in the humanitarian program from its current level of 13,750 places per annum to 20,000 places per annum would cost in the order of $1.4 billion [= $224,000 per place]…

- an increase in the family migration stream of the migration program of 4,000 places per annum would cost in the order of $0.8 billion [= $200,000 per place, and]

- the implementation of the Malaysia arrangement requires operational funding of $80 million …

- the establishment of a significant, ongoing research program … is expected to require at least $3 million per annum.

(p 144)